A rumbling begins on the convention floor. What sounds like drums begins in the distance, but you realize too late that it is a stampede. They’re chanting something as they overtake your booth in a flurry of business cards and DM’s:

“DO YOU NEED A COMPOSER?!?”

I assume this is what it’s like to interact with some Video Game Composers, so I’m beginning this handy guide for working with us, regardless of the size of your project.

Finding a composer

Chances are you know someone already, but in case you don’t, there are a few ways to scout for musical talent. First, ask your friends. You probably know someone who has a game out that featured a composer. You probably know three. If that doesn’t work, head to the meetups. ATX GameMakers is a great place to start! Composers show up at dev hangouts often enough, but you can also check audio meetups too — just be aware that you might get swamped if word gets out that you’re hiring…

You could also check out places like ProductionHUB, upwork, or Wrangle, but make these a last resort.

TIP – RED FLAGS:

- Pitching themselves before they know you

- Not making an effort to get to know you or your projects

- Zero overlap between their influences and yours

- Zero overlap between their contacts and yours

- Poor communication in person or online

- One-track mind: only talks about writing for your game

TIP – GREEN FLAGS:

- Is working on other projects

- Is professional, honest, and friendly

- Learner’s mindset

When to get a composer involved

The best game music is not an afterthought. If you are working on the visual style of your game, you can also be working on its musical style. The best soups don’t throw in the spices at the very end, they’re cooked in from the beginning. The musical world is flawlessly baked into all of Super Giant’s games because Darron Korb is there from the beginning.

That said, game development is a long process, so keep open communication about milestones, releases, pitch meetings, and so on. Don’t expect a composer to clear their calendar for two years for your project. Get their input early, and make a plan for when the bulk of the work will be done.

TIP – GET A MUSICAL SKETCH: If the scope of your project is big enough, try commissioning a “Suite” around the same time you are finalizing the visual look of your game. More on this later…

What your composer needs to know

You should meet with your composer at least three times before they ever write a single note.

First general meeting:

- Pitch your game — Why are you working on this project and what does wild success look like? How will music help?

- Discuss your influences — What games have great music in your opinion? Why? What is a game you love, but you wish had better music? What kind of music do you listen to?

- Outline your milestones and calendar — When are your important deadlines? Do your deadlines line up with when your composer is available?

TIP – MOVE FORWARD ONLY IF…

- The Vibes are good

- Your calendars can align

- Your influences have some overlap

- Their skillset is a fit

Spotting Session:

- Talk Scope — How big is this game? Which specific moments will need music? Create a list of all the unique tracks you anticipate needing.

- Have examples of similar music that you like ready. Be prepared to discuss what works about them. Will you want to feature live instruments?

- What are the most important musical moments in the game? Why?

TIP – MOVE FORWARD ONLY IF…

- You are on the same page about the vision

- You are on the same page about the scope

- You are both excited about the game

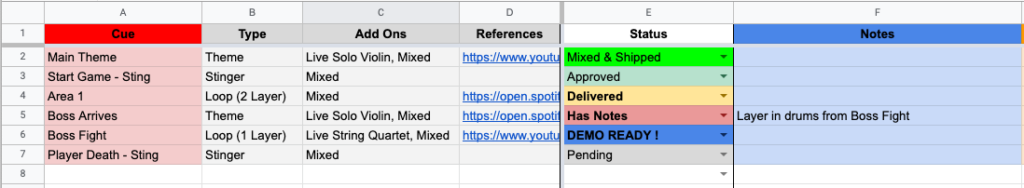

- You can fill out a cue sheet, such as the one below (Note – this cue sheet is being used mid-project to track cues.)

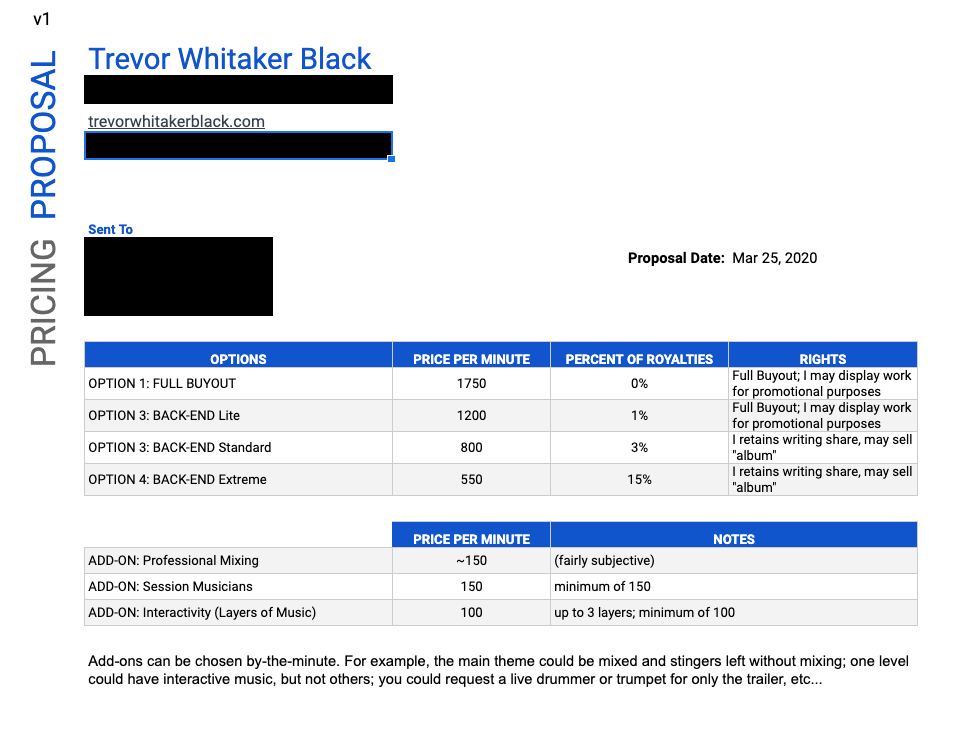

Rates, contracts, and delivery meeting:

Let’s talk money. Pricing music depends greatly upon your game and your business, and a composer will not be able to answer this question honestly until you’ve had the previous conversations. They should also be made aware of your total project budget. This meeting will be less fun than the other two, so have it over some delicious coffee or snacks. Make sure you can agree on rates, delivery dates, file formats, and what to expect when giving notes.

TIP – PAY YOUR COMPOSER BACK END: Music makes up some fixed percentage of the work that goes into a game, but the value of a game is determined by how much it sells. If you get a few steam downloads your game is worth $10,000. If your game is on XBox Gamepass, it’s worth a half of a million dollars. Your team should be paid accordingly.

Finally, draw up some simple contracts to reflect these agreements. There are templates that might work for you on LegalZoom, or there may be an entertainment lawyer lurking around ATX GameMakers!

When to get a composer involved

Now’s the time for a “Suite.” This term comes from my previous world — film music. A suite is a longer cue that will help flesh out the sound of your game. Ask your composer to take you on a journey through all possible sounds of your game in a few minutes. Often, this will become the closing-credits of your game. Suites may not be necessary for small-scale games, but if your composer will be writing more than 15-20 min of music, it might be a good call to flesh out the style up front, so they can crank out cues later. It’s also one last opportunity to make sure everyone is on the same page before the bulk of the work begins.

Provide them with visuals, concept art, cutscenes, and any other resources that bring them into the world of your game. Then sit back, and wait for the magic to show up in your inbox.

I hope to follow up this article with information on next steps, giving notes, and finishing the music for your game. See you then!

Trevor Whitaker Black began his career at Hans Zimmer’s studios in Santa Monica, and since then has worked on games for Sony, tinyBuild, and Somatone Interactive. He is currently writing for two games being developed in Austin, and he releases a weekly podcast about Faith in the Entertainment industry called The Playing God-cast. Follow him on Twitter.